In This Month’s Edition:

Editors Note

Easy Cleanup and Everyday Conservation

Gardening 101 - Hügelkultur

In The News

Reader Questions

Native Plant of the Month

Editors Note

It is the week of Thanksgiving. So far this November, the Northeast has had a week of over 70 degree temperatures, and then snow. I was still harvesting my tomatoes until last week. Climate change is here in full force.

But just like any autumn the trees are changing color and leaves are falling. As always, this gives us not only a beautiful reminder of fall, but also the headache of fall cleanup. What many don’t know, is that most of the cleanup we do is for purely cosmetic reasons. In many cases, leaving dried plant stalks intact (many insects overwinter in them), or leaf litter where it falls is significantly better for the enviroment.

That being said, we tend to see our yards and landscaping as an extension of ourselves, and don’t want to present an unkept appearance to the world. So in this edition, we are going to focus on easy ways to both decrease your fall cleanup workload while adopting practices that are better for the enviroment long term.

Easy Cleanup and Everyday Conservation

Conservation and environmentally sound gardening have unfortunately gotten the perception as both more expensive and more work than “normal” approaches. In most cases (and some would argue all), an environmentally sound approach results in less work and money spent over the long term. Instead of fighting natural systems, you encourage and support them, who then in turn do the work for you.

An easy example of this is leaf litter. Trees drop their leaves in the fall for several reasons, one being to return nutrients to a tree’s roots in order to give themselves a boost of nutrition come spring. By removing those leaves, we are taking nutrients out of the soil that needs to be ultimately replaced (usually with purchased fertilizer). Instead, we can mulch those leaves into our yards, which helps both break them down much faster (for those that want a clean looking yard), and returns the nutrients exactly where they’re meant to be. Additionally, it helps us cut down on the use of gas-powered leaf blowers, which I think everyone will agree is a good thing.

These kind of solutions are a step towards the Permaculture approach to gardening. This approach focuses on building back the natural ecosystem into a self sustaining state (like it was pre-human intervention). A successful Permaculture garden should be totally self managing, the only intervention needed would be to manage human caused issues (like invasive insects or a lack of trees) or aesthetics. For gardeners (and homeowners), you can imagine the benefit. Unfortunately, most suburban ecosystems are so badly damaged that it takes a good bit of effort to restart them.

I talk about one method in Gardening 101 below and we’ll continue to revisit this in future editions.

Easy Fall cleanup

Mulch Leaves

Two Options To Do This Easily:

Lawnmower - Set your lawnmower blades to highest setting, run over leaves until mulched.

Leaf Mulcher - You can now buy dedicated leaf mulcher machines (basically a string trimmer built into a funnel) at any of the big box hardware stores. They’re made to be ultra portable, you just carry out to where your leaves are, drop leaves into the top of the funnel, and they come out the bottom mulched.

I have heard that some people use a regular string trimmer to mulch leaves. I don’t see why it wouldn’t work, but it also likely would significantly longer than the 2 options above.

If you have someone mow your lawn for you, just asked them to do #1. I’ve found that landscapers love this option as it cuts down their time on site significantly (plus don’t have to burn gas in blowers).

Halloween Jack O’ Lanterns, Gourds, and Other Organic Fall Decorations

Pumpkins, gourds and other organic decorations are easy to deal with. Break them up with a shovel, and either just add to your compost (like you would anything else), or bury in your garden. I typically dig several shallow holes or a trench in my garden beds (3’’ - 6’’ deep), and spread the pumpkin chucks throughout before backfilling.

One note, you may see pumpkin sprouts come spring if you bury in your garden. Just yank them with your weeds.

Sticks, Branches, Tree Limbs, Whole Tree Trunks

Hügelkultur is my go to for this. (See Gardening 101 below)

Alternatively, you can mulch / chip your wood using a wood chipper and spread in your garden for your fall mulch.

Gardening 101 - Hügelkultur

Hügelkultur (German for mound culture) is a soil preparation and restoration technique that has caught on widely in the Permaculture community. It is a technique which aims to recreate the natural process of decay that occurs on a forest floor. In doing this, you are restarting the biological systems and microbiome that has been lost in most suburban landscapes. This both greatly enhances long term plant health and restores the soil biome to its proper state.

Though hügelkultur sounds intimidating, its very straight forward. At its most basic, its digging a shallow trench (just deep enough to hold your logs in place), filling with logs, branches, tree limbs, even large whole tree trunks, and then piling on progressively smaller material on top: smaller sticks, twigs, wood mulch, leaves / grass clippings / straw, compost, etc. Once everything is stacked you cover the whole mound with several inches of soil (3’’ - 6’’).

You then plant on top of it. (see diagram below)

As the material breaks down, the mound will gradually shrink and flatten, enriching the soil and supporting your plants and the microbiome for years to come.

One common hügelkultur use case for the suburban gardener is in the filling of raised beds. Using hügelkultur, you can cheaply fill a large raise bed without having to spend hundreds on bagged soil., using just the yard waste you have laying around.

Hügelkultur Raised Bed:

Start by covering the open bottom of the bed with cardboard or a thick layer of newspaper (This acts as a biodegradable weed barrier, smothering weeds until the seed bank fails).

Next, follow the same process as a hügelkultur bed; starting with large material at the bottom, you add progressively smaller material, until you reach roughly 6 inches below your target soil height.

Finally, fill the remaining 6 inches with soil. Particularly when filling a raised bed, this method is sometimes referred to as the “lasagna” technique - e.g. layering material into a pan.

Many people add a layer of compost between the non-broken down material (e.g. leaves / dried grass) and soil. I have only included compost about half the time, and haven’t seen any long term difference.

Like inground hügelkultur beds, you will notice the soil level gradually sinking as the bulk material breaks down. This is a good thing. Regularly adding more material onto the top layer of soil (compost, mulch, leaf litter, etc), will let you sustain long term living and healthy soil.

In The News

A alarming but unsurprising report made the newswire this month, finding that only 5% of all plastic in the US is actually recycled, with the remainder ending up in landfills and other dump sites.

Only 5% to 6% of U.S. plastics get recycled, new Greenpeace report finds

This has been a open secret in the recycling world since its inception (John Oliver had an excellent piece on “Last Week Tonight”), but it is heartening that it is finally becoming more mainstream knowledge.

Household plastic waste is a very small fraction compared to industrial and commercial, so in addition to trying to cut down at home, become an advocate at your workplace and in your community. Finding methods to remove plastic from both the production and waste streams will go a long way to ending the problem.

Reader Questions:

Q: “I got a houseplant as a gift, the verbal instructions were indirect light, water once a week. Its now turning brown and I don’t know what’s wrong. Also, I should mention I don’t know what kind of plant it is.”

- Zach, Washington D.C.

A: Your first step when buying or being given a plant should always be to identify it. There are many plant identification apps in the App Store, but the best I’ve found is the one that comes with both Phones and Androids. Simply take a picture of a plant, and a little “i” will pop up on or below the photo. Click it to get identification information.

When we raise plants, we are tasked with emulating their native environments as closely as possible in order to keep them healthy. I like to research and envision the enviroment they evolved in and tailor my care to that image.

For most common houseplants, that environments either the tropics or the desert. Neither of which are emulated in your typical American climate controlled home. So we do our best. Four things to keep in mind:

Repot every 18 months: Potting soil needs to be replaced every 18 months (even if the plant hasn’t outgrown its pot). Potting soil loses its nutrition over time, and biological waste and fertilizer salts build up. Without a functioning ecosystem to restore the soil and handle the waste, we need to do it ourselves.

Humidity: Tropical plants are used to a much higher ambient humidity than you typically want in your home. During the summer months this isn’t normally a problem, but during winter, particularly in cold regions, it is. Spraying with a water mister or setting a humidifier next to your plants are both common solutions.

Water: Make sure you’re watering correctly. Remember: in winter’s low humidity, pots dry out faster. See our Watering 101 for more.

Light: I have found most houseplants are in the wrong light. People typically over or underestimate how much light there is in a given spot. As a general rule:

Full sun: 8+ hours of direct sunlight (likely impossible inside, unless you have a greenhouse)

Part sun: 4 - 6 hours of direct sunlight

Part shade: 2 - 4 hours of direct, morning sunlight. Indirect rest of day

Indirect light: Put a piece of white paper over a window in direct sunlight. The amount of light coming through the paper is what is considered “Indirect”. 4 - 6 hours of that is needed daily

Q: “We bring our houseplants outside for the summer, but have always struggled with when to bring them inside during the fall. I’ve heard that some plants need the cold, but I’m guessing many of our house plants do not. When should we be bringing them in?”

- Hank, CT

A:

For most houseplants, once nighttime temperatures start dropping to 60f its time to bring them in. Many can’t survive exposure below 55f, so its not worth risking a sudden overnight cold shock.

You’re right that some plants need annual exposure to cold. This is referred to as “chill hours”, and is the amount of time a given plant needs below 45F during the winter. This is especially important for many fruit trees (and bushes). Not reaching their minimum chill hours will lead to limited to no fruiting the next growing season. (e.g. most blueberries varieties need 500 chill hours or more).

The tricky part is balancing the need for chill hours with it being too cold outside for the given plant to survive. What many people do is leave those plants outside until temperatures are in the 40s at night, then move the plants to their garage or shed (assuming it stays in the right temperature range). Once the plant has gone dormant for the winter, it doesn’t need sunlight until spring so find the ideal spot and let it rest. Read our guide to overwintering here.

Don’t forget to water! Plants still need water in the winter, just much less.

Have a garden question you want answered in a future newsletter? Email us at: contact@overscheduledgardener.com

Native Plant of the Week:

Chokeberries

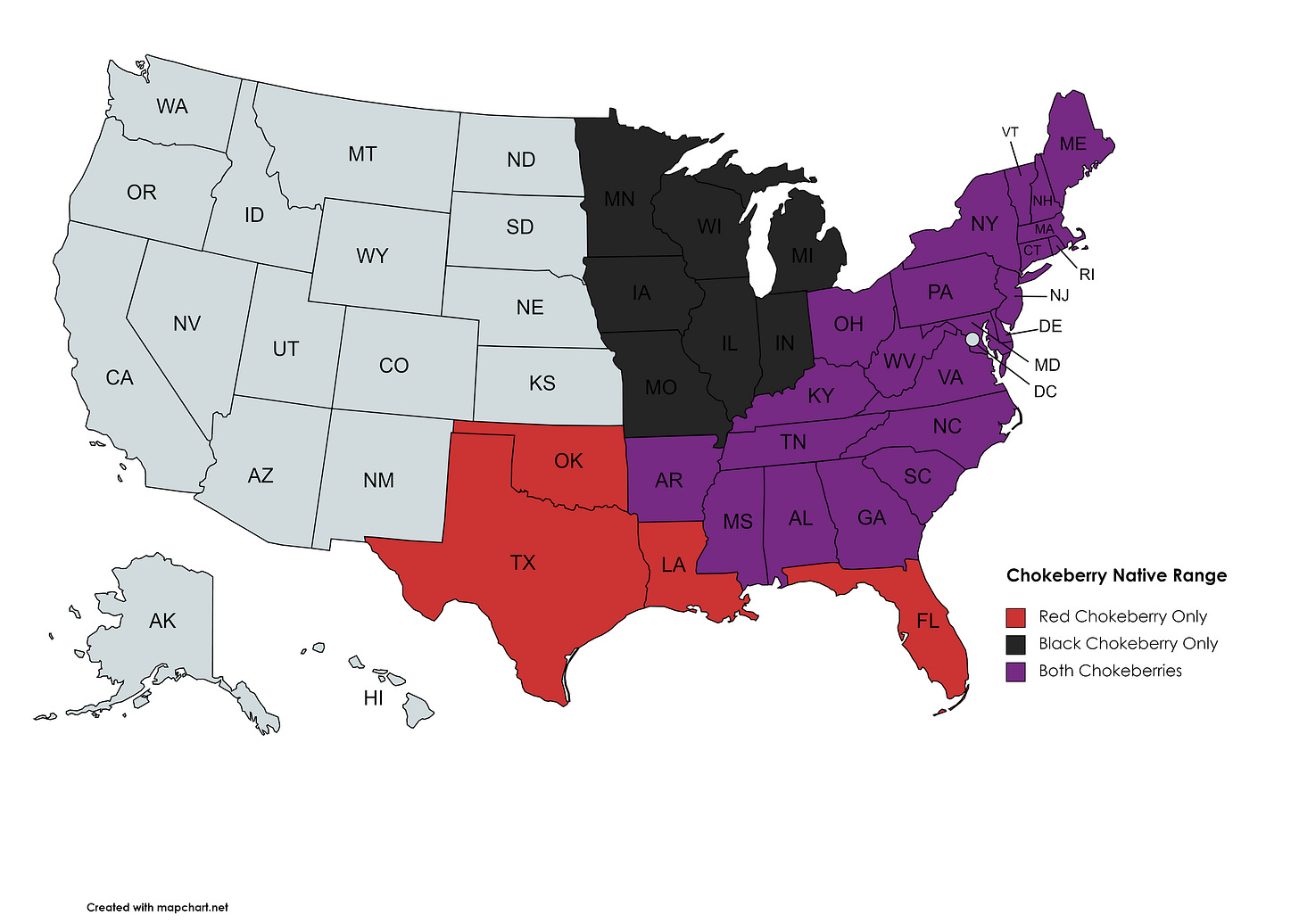

Aronia arbutifolia - Red Chokeberry

Aronia melanocarpa - Black Chokeberry

Type: Flowering Shrub Duration: Woody Perennial Sun Need: Full Sun - Part Shade Water Need: Moist soil - Drought and flood tolerant once established Zones: Red: 4 - 9 Black: 3 - 8 Bloom Time: Spring Bloom Color: White, very showy Availability: Increasingly common Cultivars: Red: "Brilliantissima" Black: "Autumn Magic", "Viking" Natural Enviroment: Open clearings, woodland thickets, marsh edges, bogs Biodiversity Supported: Pollinators & Birds - Spring pollinator support, Red Chokeberries are important fall food source for migratory birds

Native Range:

Good For:

Ornamental plantings, flower gardens, pollinator gardens, wildlife gardens, wetland restoration, borders, mixed hedges

Description:

Covered in big, showy, white flowers come spring (many say it reminds them of Japanese Cherry Trees), green glossy foliage all summer, and spectacular red, orange, and purple leaves in the fall, Chokeberries are held up as a shining example of a more attractive native plant being replaced by less attractive imports for no particular reason. Named for the astringency of their berries, they are edible (despite the name), and are traditionally used in jams, preserves, juices, and pies.

These two native Chokeberries differ in coloration and habit, with:

Black Chokeberry having purple-black berries; Red Chokeberry having red berries

Black Chokeberry having more purplish-red fall foliage; Red Chokeberry having bright red and orange fall foliage.

Black Chokeberry fruit maturing in late summer, then dropping; Red Chokeberry fruits maturing in fall and persisting through winter (if not eaten)

Black Chokeberries staying rounder and fuller; Red Chokeberries growing more upright (tall and narrow) with a bare base

The two species hybridize readily, with hybrids being referred to as Purple Chokeberries.

Their flowers are a major source of pollinator food in the spring, and their berries serve as an important food source for birds, making this a solid addition to any wildlife garden.

Both are increasingly being seen as an ornamental addition to home landscapes, with the Red chokeberry “Brilliantissima” and Black Chokeberry “Autumn Magic” cultivars (among many others) being bred for this purpose.

How To Use:

Plant as the centerpiece of a native grouping, interspersed in a mixed border or hedge. Use Red Chokeberries where the ground stays wetter and you will have plantings in front of it (to hide the bare base). Use Black Chokeberries where the base will be exposed. You want both species very visible in spring and fall to highlight their beauty.

Planting:

Normal perennial approach: dig a hole twice the diameter of the pot, put the plant in the hole, and backfill the soil. Keep the soil moist until established. Chokeberries like moist, well drained soil, but can tolerate occasional flooding and drought once established. They are known to be very hardy plants even in less than ideal conditions.

Key Purchasing Tip:

When purchasing, make sure to check that the scientific name matches the name above. Nursuries will often bunch all chokeberries together.

Thanks for reading The Overscheduled Gardener! Subscribe to get this newsletter directly to your inbox